In conversation with Miguel Noya

Venezuelan early ambient musician and field recordist discusses his new album

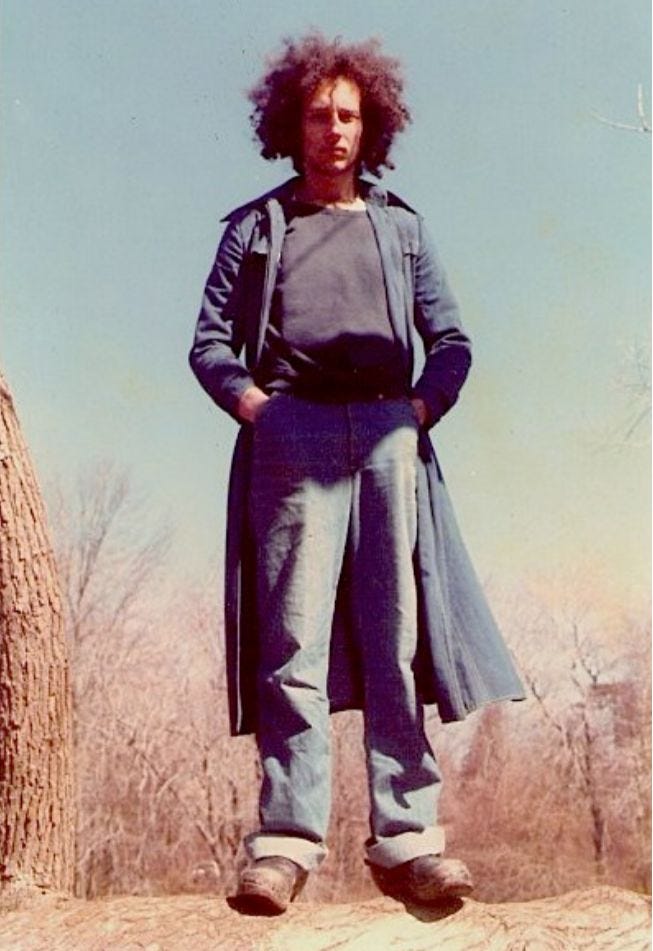

Miguel Noya (b. 1956, Caracas, Venezuela) was and remains a pre-eminent figure in Latin American electronic music. Since the early 1980’s, he has created remarkably original recordings for analogue synthesis and early computational tech under his own name, with groups, and in commission for film, television, stage production, and other media. He holds dual degrees from MIT and Berklee, and continues to teach audio synthesis in various institutions across the world. I came to Noya’s work via my interest in the music of his friend Jorge Reyes, an early Mexican ambient musician who passed away in 2009.

In early 2020, after months of calls, emails, planning, and preparing - just as lockdown had begun locking down - Phantom Limb released a 2xLP retrospective of Noya’s catalogue named Canciones Intactas: The Music of Miguel Noya. It is brimming with deeply learned creativity, an intuitive harmony of sound and mood, and a mesmeric world-building that could only have come from the singular mind of Miguel Noya.

Earlier this month, Miguel released a glorious and powerfully immersive album of field recordings taken on location in his farmland in rural Venezuela, where the internet regularly blacks out and life is in constant push and pull with nature. Miguel and I talked via WhatsApp, discussing this new work and our collective experience in releasing his records.

JV: Tell us about your new record. What led you to field recording?

MN: Biofonía is the Spanish word for “biophony”, which is the term for sounds generated by biological organisms in a given environment. This project came to be part of a process after our conversation a year ago. You asked me to do an album of sound field recordings, to be released digitally. I was already configuring an album that included some of my natural sounds library from our home in the countryside of Carabobo’s High Valley.

These sounds I have collected in nature around the farm. For an earlier part of the project, Biophony I, alongside natural sounds I created electronic-ambient pieces composed, performed, and recorded in my personal studio. I still remember playing music along with evening and nocturnal sounds all around the house. A true multi-intense orchestra of insects and different nocturnal beings.

Also, another influence to embrace the possibility of an album of only natural sounds was some artwork by my son Thomas. He used some of the library of sounds in his project Time is Inherently Cruel. His project employed these takes and some audio digital processing. It was interesting idea and I liked the result of combining the sounds with visuals to create digital art. I also have to refer to the fact that using sounds of reality and natural spaces has been part of my personal conceptual, performance, and musical work since the early 80s. You can find some examples in many of my pieces across different albums and performances.

To embrace a project where the nature sounds would be the principal content has been a very interesting challenge and a fun process. The main thing that led me to field recording is the personal desire to learn how to listen and find music in the reality we live in.

Recently I have discovered the work and ideas of Pauline Oliveros, and her concept of deep listening. I got her concept in our parallel careers as electronic music composers, producers, and performance artists. I guess I learnt to listen. The paradox is that as a strange fact I never knew about her work until recently. This is an idea that moves me.

JV: How do you apply your creative process to field recording? How do you view your role as a musician in the practice of field recording?

I would consider that the creative part is exactly what I feel and what I perceive in the process of listening and paying attention to the diversity of sounds: how are they generated, the characteristics, and the very profound immersive feeling coming specially from a very complex specialisation. Also, at the same time focusing on the thoughts about what I am listening to, trying to find and feel music. The music and the moment; looking for coincidences in the roots of the language.

My role as musician then is the perceptive process of an individual trained in the field. “Perception” is the key word.

JV: When do you find yourself in field recordist mode vs composer mode? Could you choose between them?

MN: When in I am in the field and when my conscious is focussed, the recordist and composer modes go together. And, yes, sometimes I can choose which one I am, depending on the moment. The first step is to listen and get the feeling. Then I enter into the craft. Sometimes I set up the recording process first, then I try to connect myself to the feeling the sounds and the sound field induces me to feel. This last moment is the one that determines and defines which of the recordings are the ones to consider.

JV: Tell us about your history in electronic music. Tell us about your 2020 compilation album Canciones Intactas.

MN: My history in electronic music is kind of a long path. My first experiments were done in Valencia, Venezuela, in the early 70s, like ‘73 or ‘74. I began as child by studying theory, solfeggio, and piano in a music school. As a teenager in late 60’s, my span of interest expanded from classical music into rock, especially non-commercial sounds like the psychedelic and hard rock movements. The Beatles (their albums after Revolver), Pink Floyd, Zappa, and prog rock bands like Yes, Van der Graft Generator, ELP, Genesis, King Crimson, and many others inspired me to look for new sounds, new forms to generate and manipulate sounds. My first experiments included manipulating a tape reel, processing an electric guitar.

I had no idea at all of the concréte or electronic music movements then. We were living in Valencia, which was a small, strange city. A lot of music and musicians and information about them was not available. Those bands were never played in radio stations. Only the Beatles. Once I discovered these movements, I started to get interested in the new sounds and electronic music, especially after discovering Tangerine Dream, Stockhausen, Vangelis, Wendy Carlos, Tomita and a few others. This was around 1973 and beyond. I guess my real path started when my brother and I bought our first synthesiser, a Roland SH-3, in 1976. Immediately, electronic music started to manifest in my work, in the form of small pieces and performing live electronic music mixed in with rock bands and in theatre productions.

I left Valencia in 1978 and entered the Berklee College of Music. Coincidentally, they had just opened a major in Electronic Music. I was very involved in the studio and the Electronic Music Department. Later I had the chance to enter the special program of Computer Sound Synthesis under Barry Vercoe at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I was lucky enough to see Max Mathew, Marvin Minsky, and Charles Doge in person among others. I had a classmate named Claude Larson (Klaus Netzle); we became friends and in summer 1981 I got to know his studio in Munich. He had a very cool space that included a Fairlight CMI and a Roland MC8 with large modular 700. In the same year I met Paul Godwin, another Berklee College student, who became my closest friend and brother in music. We formed a techno-punk duo named Dog 46. We made some recordings using mostly analog synthezisers with vocals. We played a couple small shows in Boston same year. The band reunited again in Caracas in 1988-9 and changed its name to Dogon.

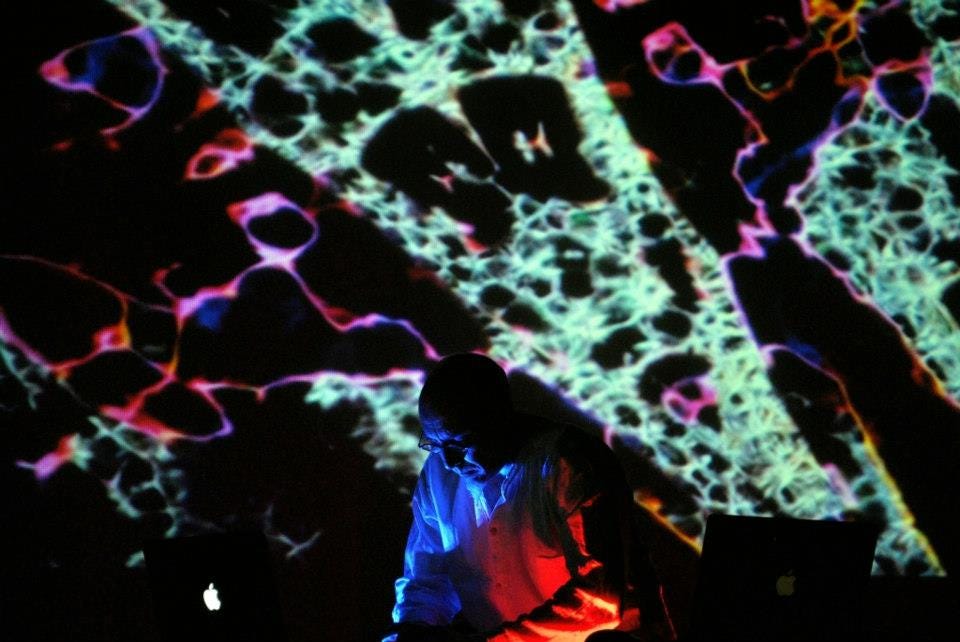

Godwin settled in San Francisco in 1995, but the band is still active. In 1996, we performed at the Caracas festival La Otra Música. It was a livestream, both of us playing remotely and simultaneously, Paul in San Francisco and me in Caracas. The concert went under the title Netloops; I think is considered one of the first ever livestreamed performances.

I returned to Venezuela early 1982 and released my first album Gran Sabana in 1984. Since then I have been creating, composing, and performing electronic music nonstop.

In 2019 I was on a lecture tour in Spain and working in a recording project in Berlin with Eternal Return when you contacted me, interested in listening to my catalog. You had the idea of reissuing some of my 80’s work. I found it interesting that the playlist you sent me included part of a conceptual art project called PsychoMusic. The original project was design for an art Gallery in Caracas and the exhibition was called Artefacto. And also material from Esferas Vivientes, which was my second album, originally released on cassette only. I found it quite surprising that your choices comprised music mostly from the period of 1986 - 1990.

It was great for me to work with you and Phantom Limb. It brought a connection with England that never crossed my mind because is where actually came 90 % of the music that influenced me in my adolescence and also got me to be very curious about the way they manage creativity in music.

It was at Café OTO where we met in person for the first time, just before the pandemic. The reissue album Canciones Intactas was a peak in my personal and professional life. It sounds incredible, remastered from analog reel to reel 1/4 inch 4 tracks recordings.

JV: Tell us about growing in Venezuela and how this environment influences your creative practice.

MN: I was born in Caracas, which is the capital of the country. We moved to Valencia, in the state of Carabobo, in 1961 when I was only 4 years old. We used to live in a downtown classic colonial house. The city was quite tranquil but experienced a lot of industrial development, half rural in some places. It had some very deep historical background but you could feel it was distant to the size and activity of Caracas. The cultural aspect of this society was strange.

The first concert I attended was a solo piano recital at the Teatro Municipal. It was a concert by Claudio Arrau, a very prestigious and famous piano player. The program included Debussy Feux D'Artifice. So that left a powerful mark on me. I still remember it, even though I was only 7 years old. It was the same year I entered the music conservatory.

Later on, when I was already playing music and starting my electronic explorations, I had the chance to attend a free jazz concert by the Albert Mangelsdorff Quintet, which ended up as a quartet because the piano player Joachim Kühn could not perform as it was not possible to tune the piano (it was in really bad shape). The concert was a total revelation for me. So I guess these kind of events describe Valencia and the Venezuela where I grew up. Retro in some senses but open and universalist in others. You see a very unusual tropical country open to modernity now lost in translation.

JV: What else do you do in your life? How do these practices inform your music? Your family is also closely involved in music.

MN: My life is active in a very rich way. I continue undertaking personal research on music and technology, performing, composing. I still participate in collaborations with friends here and in different part of the planet, writing words and ideas. I collaborate with dancers and choreographers. And I am a teacher of Electronic Music Production, Synthesis, and Electronic Music Composition privately and at Audio Place. I was also former teacher at TAS Taller de Arte Sonoro 1987-97. That, and also I have a long term as a farm worker, where most recordings for Biofonía come from. This is very physical and demanding work.

My family is close to music and the arts. My grandfather used to play the piano (by ear). So, we in the family had to attend the music conservatory from early ages. It was my mother’s command. We are seven siblings, and all of us in one way or another went through the language of music. I had a brother who played the oboe, a sister who played viola, and my mentor and older brother Francisco is a successful orchestral conductor and currently music director of the Boston Civic Orchestra. He and I have an electronic project 1 ONCE 1, with an album out soon.

JV: Where do you see the future of recorded music?

MN: Well, let us start by asking the question: where is the present of recorded music? It is a crazy moment, with all the tools for producing and recording in a world where technology has been totally democratised. We have to consider the high level of many super talented young musicians everywhere. I guess we are totally numb from the amount of data and information so easily available everywhere.

Because I do think that music is kind of a quantic field that resonates with humans (also with some many other forms of life), I guess there will always be a future for music. But I do think the main event will continue to be live action. The real-time contact of audience and performer.

I think recorded music will not disappear, and will be available not only online but in many more media including new models like implanted devices. You see you still can find vinyl, cassettes, minidisc, and other formats many people thought would disappear. So maybe we can imagine new ways to transmit recorded music into really crazy devices implanted in the brain. Let us open our imagination.

Maybe AI will take over, but I don’t believe that music will decide to participate in this new medium. It lacks true feeling.

JV: How are you feeling about the state of the world? Are you able to disconnect? How do you feel the political situation in Venezuela affects or is seen by the rest of the world?

MN: The situation here is an extreme not easy to digest. There is not too much I can say without taking a dangerous risk. The rest of the world is now reacting, but not fast enough. In some cases, instead of helping, they are taking advantage and learning how to control power, learning from our experience in Venezuela.

The state of the world is totally chaotic everywhere, but it is not surprising for me. We have read so many authors who predicted possible future scenarios that now have become for real. Orwell, Huxley, Dick, Wilson, McKenna, Leary, Asimov, Lessing, among many. Being a very sensitive and emotional human being, sometimes I feel totally devastated of course, but this general chaos has been tested here in Venezuela for many years. So in one way I am kind of trained. It is very strange that it’s happening in what we thought were the civilised countries called the “First World”.

Are we becoming a low end civilisation? Do we now have “better” music, arts, poetry, and humans? Yes, everything is replicating, reproducing, and generating, but do we lack the level of consciousness to handle this moment of development?

We can not generalise the human condition everywhere all the time. I would say “reality”, as we assume we know, is melting down because lots of humans are not prepared to handle the speed of development. Quoting Marshall McLuhan's concept of "all extensions are amputating" suggests that every technological or cultural extension also leads to the loss or modification of something else.

Let us apply this to AI: locality is the right answer, we have to be able to function in our localities. Learn how to remember how to function with no extensions. All the answers are in the technology of nature and the human body.

maravillosa entrevista, Maestro!